| |

|

The stage for a confrontation years in the making was finally set last week, when the Greek government failed to repay a $1.7 billion USD instalment and announced its intention to hold a referendum on whether or not to accept a bailout package which Eurogroup creditors insist be contingent on further austerity measures the leftist government there was loathe to implement. While some likened the latest twist in the ongoing crisis as a game of chicken to see which side blinks first, it increasingly looks like the rest of the currency union's patience is beginning to wear thin. Eurozone leaders last week warned that a "no" vote would only serve to isolate Greece and drive it further into insolvency. Evidently it wasn't enough to convince Greeks however, who have grappled with levels of unemployment which now see 1 in 4 people jobless, as well as youth unemployment just shy of 50%, for they voted overwhelmingly in favour of rejecting the deal as is. A significant reason why was the successful narrative painting the referendum as the reassertion of the democratic process in negotiations, which many in the country view as the realm of European technocrats and politicians more interested in their European Union pet project than the plight of the average Greek. When the results were announced, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras was jubilant, and for good reason; a "yes" vote would have been disastrous for his vehemently anti-austerity party, who were key in spinning the ultimately winning narrative. To illustrate, the Minister of Labour later said "I believe there is no Greek today who is not proud, because regardless of what he voted he showed that this country above all respects democracy."

But what of the already dire situation which is now only set to become worse? After the ECB cut emergency liquidity in response to Greece defaulting, the government was forced to implement capital controls, something which should have been done months earlier while the banking system was still receiving regular injections of liquidity. While tightly controlling the flow of money out of the system has bought Greece some time, it has done little to stave off a potential banking collapse, with most estimates forecasting that the banks will run out of cash on Monday. Some have suggested that the use of "scrips", or IOUs presents a potential way forward in the event of a now inevitable liquidity crunch, pointing out that such a system was successful in 2009 when California was undergoing significant economic turmoil. Ignoring the fact that the system was only in place for two months (even then banks had ceased purchasing scrips in exchange for USD, fearing potential overexposure) and that Californians were okay receiving incomes, pensions and benefits in IOUs was in part because of 3.75% annual interest to be paid upon maturity, the fact of the matter is that Greece's creditworthiness is such that borrowing on such a scale is virtually impossible. July 13th is when the government must pay salaries, benefits and other liabilities, a de facto deadline which will certainly test the mettle of Tsipras's government, whose officials have repeatedly insisted they can get a new deal done within a 24-48 hour time frame.

And that claim raises yet another issue. The government got a favourable result in the referendum by promising to extract greater concessions from the Eurogroup, something which it must now do. It wants budgetary restraint on its terms, favouring an increased tax net rather than further cuts to social programs that will only be more necessary as the economy's plunge accelerates. While austerity failed to cut into Greece's debt at the anticipated rate, European leaders would likely lay the blame for that at the feet of successive Greek governments which failed to improve competition, fight corruption and combat rampant tax evasion, all of which played a role in turning the aftershocks of the 2008 global financial crisis into a six year recession. As such, it is hard to imagine any of the involved parties being in a charitable mood come Monday. The initial responses to the referendum and Greek entreaties for continued talks only confirm this grim assessment. Eurozone finance ministers shot down the idea of emergency meetings Monday, point blank saying they "would not know what to discuss". The ECB reluctance to agree carte blanche to continue providing emergency funds to Greek banks, despite the potential for such a move to cause the country to collapse, speaks volumes to the fact that the Greek debt crisis has reached uncharted territory; and the rest of Europe isn't ruling out anything.

"You have to do things that are going to be fundamentally impossible to explain to people" - Former U.S Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner

Taken alone, the jubilation in Athens today could have made one forget about how Greece currently sits at the precipice of total economic collapse. Retailers in the city go sometimes days without a single customer, and even butchers and grocers who still do brisk business are feeling the pinch from their suppliers abroad, who are beginning to demand payment upfront. The now uncertain future of the country's economy has rendered Greeks unable to import everything from simple foodstuffs to desperately needed medical supplies. The fact that many in the country didn't know what exactly they were being asked to vote "yes" or "no" to, or that the government there won by appealing to Greeks' wounded pride, all signal a dark future ahead for Greece. Tsipras's referendum might have been a win for democracy, but it carries with it a significant price; the rest of Europe is now reconsidering its support for the Greek economy, and behind the government's hopelessly optimistic assessment that it can get a deal done in a matter of days, as opposed to weeks, complete silence about the coming unravelling of the country's economy makes the "democracy at work" narrative being peddled ring hallow. Successful bailout programs, such as TARP in the United States as well as Sweden's rescue of its banking sector in the 90s, were both reviled by the public when they were first unveiled. And yet the architects of such programs are now lauded for their work, and the model of isolating toxic assets in "bad banks" first pioneered by Bo Lundgren in Sweden has been emulated in several debt crises since.

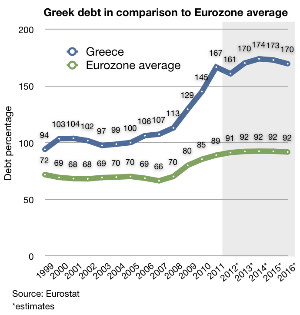

Antagonizing your creditors is never a good idea, (something Argentina knows very well) even when their methodology isn't working as intended. Should a productive relationship be reestablished however, there may be hope yet for Greece. Recently the IMF released a white paper containing its latest analysis of Greek debt, and came to the conclusion that given the sheer heft of Greece's debt load, its unlikely Greece's creditors will ever be repaid the entirety of the sum they are owed. Among some of the figures thrown out, perhaps the most interesting was the fund's assessment of Greece's ability to both service and pay down its considerable debt. In the IMF's estimation, the country not only requires a third bailout to the tune of $67 billion USD, but that the maturities on its debt obligations be doubled to 40 years. The hope for Greece however, lays in what was said next; it is vital that a significant portion of Greece's debt be written off, to the tune of $59 billion USD. This makes sense, given that the economy will continue to suffer for the foreseeable future. A restructuring of the country's debt would allow the Greek government, which has drained funds from areas such as healthcare and education in order to make repayments, to further stabilize the economy without having to resort to further cuts to important social programs. Surprisingly, it was the Eurozone which first proposed such a move three years prior, in exchange for reforms. Should such terms be reintroduced, the EU will get the fundamental changes to the Greek economy it wanted, and Greece gets more favourable terms in the form of long term debt relief. While by no means sufficient, such a deal would firstly put Greece on a path to recovery, and provide a roadmap for the Greek economy going forward. But it simply cannot happen if the current admittedly rather frosty state of affairs between involved parties persists.

The current austerity regime is far from perfect, having misjudged the impact of cuts and overestimated the Greek economy's capacity to grow in order to compensate. And yet the wholesale rejection of austerity, combined with a seeming abdication of responsibility on the part of the Greek government for the role of its fiscal policies in initiating this crisis reflect a seeming dissonance between Greece and its fellow EU confederates. One argues that a messy and fraught economic issue should be placed in the hands of those who simply cannot hope to understand it, while the other believes that such problems best be left to the brightest minds. Greece has no clear path forward, but a messy divorce from the eurozone, now a real possibility, certainly will not help matters. Sensible solutions have been put forward for years, now both sides simply need to listen.

No comments:

Post a Comment